How Many Pounds Can a Sled Dog Pull

Carrying the postal service and the weekly Klondike Nugget, this service covered all the creeks adjacent to Dawson. The service was established by Jean (or Factor) Allen in 1898

A sled canis familiaris is a dog (featuring Siberian Husky, Alaskan husky or Alaskan Malamute) trained and used to pull a state vehicle in harness, most commonly a sled over snow.

Sled dogs accept been used in the Chill for at to the lowest degree 8,000 years and, along with watercraft, were the only transportation in Arctic areas until the introduction of semi-trailer trucks, snowmobiles and airplanes in the 20th century, hauling supplies in areas that were inaccessible by other methods.[1] They were used with varying success in the explorations of both poles, as well as during the Alaskan gold rush. Sled domestic dog teams delivered mail service to rural communities in Alaska, Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut. Sled dogs today are still used by some rural communities, specially in areas of Russia, Canada, and Alaska as well equally much of Greenland. They are used for recreational purposes and racing events, such as the Iditarod Trail and the Yukon Quest.

History [edit]

Sled dog wearing harness during the Jesup Expedition in Siberia

Sled dogs are used in countries such equally Canada, Sápmi (Lapland), Greenland, Siberia, Chukotka, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Alaska.[two]

A 2022 study showed that nine,000 years ago, the domestic canis familiaris was present at what is now Zhokhov Island, northeastern Siberia, which at that time was connected to the mainland.[iii] The dogs were selectively bred as either sled dogs or hunting dogs, implying that a sled dog standard and a hunting canis familiaris standard co-existed. The optimal maximum size for a sled dog is 20–25 kg (44–55 lb) based on thermo-regulation, and the ancient sled dogs were between 16 and 25 kg (35 and 55 lb). The same standard has been plant in the remains of sled dogs from this region 2,000 years ago and in the modern Siberian Husky breed standard. Other dogs were more than massive at 30 kg (66 lb) and appear to be dogs that had been crossed with wolves and used for polar bear hunting. At expiry, the heads of the dogs had been advisedly separated from their bodies past humans and was thought to be for ceremonial reasons.[iv]

Greenland [edit]

Dog sledding is yet commonly used for transportation in parts of Greenland

The Greenlandic Inuit take a very long history of using sled dogs and they are still widely used today. As of 2010, some eighteen,000 Greenland dogs were kept in western Greenland north of the Arctic Circle and in eastern Greenland (considering of the effort of maintaining the purity of this culturally important breed, they are the simply dogs allowed in these regions) and about half of these were in active use as sled dogs by hunters and fishers.[v] As a result of reduced sea ice (limiting their area of use), increasing employ of snowmobiles, increasing dog nutrient prices and disease among some local dog populations, the number has been gradually falling in decades and by 2022 there were fifteen,000 Greenland dogs. A number of projects have been initiated in an effort of ensuring that Greenland's canis familiaris sledding civilisation, knowledge and utilise are non lost.[6]

The Sirius Patrol, a special forces unit in the Danish military, enforces the sovereignty of the remote unpopulated northeast (substantially equalling the Northeast Greenland National Park) and bear long-range dog sled patrolling, which also record all sighted wild fauna. The patrols averaged 14,876 km (ix,244 mi) per year during 1978–1998. By 2011, the Greenland wolf had re-populated eastern Greenland from the National Park in the northeast through following these domestic dog-sled patrols over distances of upwardly to 560 km (350 mi).[seven]

Due north America [edit]

Labrador huskies existence fed by Inuit

In 2019, a study plant that those dogs brought initially into the North American Arctic from northeastern Siberia were subsequently replaced by dogs accompanying the Inuit during their expansion beginning 2,000 years ago. These Inuit dogs were more than genetically diverse and more than morphologically divergent when compared with the earlier dogs. Today, Chill sledge dogs are the terminal descendants in the Americas of this pre-European dog lineage.[8]

Historical references of the dogs and domestic dog harnesses that were used by Native American cultures date dorsum to earlier European contact. The use of dogs equally draft animals was widespread in N America. There were two principal kinds of sled dogs; ane kind was kept by littoral cultures, and the other kind was kept past interior cultures such every bit the Athabascan Indians. These interior dogs formed the basis of the Alaskan croaking. Russian traders post-obit the Yukon River inland in the mid-1800s acquired sled dogs from the interior villages along the river. The dogs of this area were reputed to be stronger and meliorate at hauling heavy loads than the native Russian sled dogs.[9]

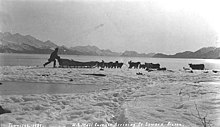

US mail carrier and dog sled team arriving at Seward, ca 1912

The Alaskan Gilt Rush brought renewed interest in the utilize of sled dogs as transportation.[nine] Virtually gold camps were accessible simply past dogsled in the winter.[10] "Everything that moved during the frozen season moved by canis familiaris team; prospectors, trappers, doctors, postal service, commerce, merchandise, freighting of supplies … if it needed to motility in winter, it was moved past sled dogs."[9] This, along with the dogs' use in the exploration of the poles, led to the late 1800s and early 1900s being nicknamed the "Era of the Sled Dog".[11]

Caption reads "Set for The Long Mush, Seward, Alaska" (click photo for further information) ca 1914

Sled dogs were used to deliver the mail in Alaska during the late 1800s and early 1900s.[12] Alaskan Malamutes were the favored breed, with teams averaging eight to 10 dogs.[12] Dogs were capable of delivering mail in conditions that would finish boats, trains, and horses.[12] Each team hauled between 230 and 320 kg (500 and 700 lb) of mail service.[12] The mail was stored in waterproofed bags to protect information technology from the snow.[12] By 1901, dog trails had been established forth the entirety of the Yukon River.[12] Mail service commitment by dog sled came to an terminate in 1963 when the last mail carrier to use a dog sled, Chester Noongwook of Savoonga, retired.[12] He was honored by the United states Mail in a ceremony on St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Bounding main.[12]

Airplanes took over Alaskan mail delivery in the 1920s and 1930s.[nine] In 1924, Carl Ben Eielson flew the first Alaskan airmail commitment.[13] Dog sleds were used to patrol western Alaska during Globe War Two.[thirteen] Highways and trucking in the 40s and 50s, and the snowmobile in the 50s and 60s, contributed to the refuse of the working sled dog.[ix]

A sled dog team of six white huskies hiking in Inuvik, Canada

Recreational mushing came into identify to maintain the tradition of dog mushing.[9] The want for larger, stronger, load-pulling dogs changed to one for faster dogs with high endurance used in racing, which caused the dogs to become lighter than they were historically.[9] [fourteen] Americans and others living in Alaska and so began to import sled dogs from the native tribes of Siberia (which would later on evolve and go the Siberian Husky brood) to increase the speed of their ain dogs, presenting "a direct contrast to the idea that Russian traders sought heavier draft-type sled dogs from the Interior regions of Alaska and the Yukon less than a century earlier to increment the hauling capacity of their lighter sled dogs."[9]

Outside of Alaska, dog-drawn carts were used to haul peddler'due south wares in cities similar New York.[15]

Alaska and the Iditarod [edit]

Col. Ramsay'southward entry, winning dog sled team of the third All Alaska Sweepstakes, John Johnson, commuter ~ c 1910

In 1925, a massive diphtheria outbreak crippled Nome, Alaska. There was no serum in Nome to care for the people infected by the illness.[13] There was serum in Nenana, but the town was more 970 km (600 mi) abroad, and inaccessible except by dog sled.[13] A dog sled relay was fix upward past the villages between Nenana and Nome, and 20 teams worked together to relay the serum to Nome.[13] The serum reached Nome in six days.[13]

The Iditarod Trail was established on the path between these two towns.[13] Information technology was known every bit the Iditarod Trail considering, at the time, Iditarod was the largest town on the trail.[13] During the 1940s, the trail fell into decay.[13] However, in 1967, Dorothy Folio, who was conducting Alaska'southward centennial celebration, ordered 14 km (9 mi) of the trail to exist cleared for a domestic dog sled race.[thirteen] In 1972, the US Army performed a survey of the trail, and in 1973 the Iditarod was established by Joe Redington, Sr.[13] [16] The race was won by Dick Wilmarth, who took three weeks to complete the race.[xiii]

Musher and dogs enter Iditarod finish chute

The mod Iditarod is a 1,800 km (1,100 mi) endurance sled dog race.[16] It ordinarily lasts for ten to eleven days, weather permitting.[16] Information technology begins with a formalism kickoff in Anchorage, Alaska on the forenoon of the starting time Saturday in March, with mushers running 32 km (20 mi) to Eagle River forth the Alaskan Highway, giving spectators a chance to encounter the dogs and the mushers.[17] The teams are and so loaded onto trucks and driven 48 km (30 mi) to Wasilla for the official race start in the afternoon.[17] The race ends when the terminal musher either drops out of the race or crosses the cease line in Nome.[16] The winner of the race receives a prize of Usa$l,000.[16] It has been billed equally the "Globe Series of mushing events"[xviii] and "The Terminal Great Race on Globe".[19]

Antarctica [edit]

Roald Amundsen's Antarctic expedition

The first Arctic explorers were men with sled dogs.[20] Due to the success of using sled dogs in the Arctic, it was thought they would be helpful in the Antarctic exploration also, and many explorers made attempts to use them.[twenty] Sled dogs were used until 1992, when they were banned from Antarctica by the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty[20] over concerns that the dogs might transfer diseases such every bit canine distemper to the seal population.[21]

Carsten Borchgrevink used sled dogs (Samoyeds) in Antarctica during his Southern Cross Expedition (1898–1900), but information technology was much colder than expected at Cape Adare.[xx] The dogs were used to working on snow, not on ice, in much milder temperatures.[xx] The dogs were besides inadequately fed, and eventually all of the dogs died.[twenty]

Erich von Drygalski used sled dogs in his 1901–1903 expedition, and fared much improve because his dogs were used to the common cold and he hired an experienced domestic dog handler.[20] His dogs were allowed to breed freely and many had to be shot because there was no room on the transport to take them home.[twenty] Many that were not shot were left behind on the Kerguelen Islands.[twenty]

Otto Nordenskjold intended to utilise sled dogs in his 1901–1904 trek, just all but iv of his dogs died on the journey south.[xx] He picked up more dogs in the Falklands, but these were all killed upon his arrival by Ole Jonassen's huskies, as Ole had not bothered to tether his dogs.[20] These huskies were later able to pull 265 kg (584 lb) over 29 km (xviii mi) in three and a one-half hours.[20]

Robert Falcon Scott brought 20 Samoyeds with him.[xx] The dogs struggled under the conditions Scott placed them in, with four dogs pulling heavily loaded sleds through 45 cm (eighteen in) snow with bleeding feet.[20] Scott blamed their failure on rotten dried fish.[20]

Douglas Mawson and Xavier Mertz were part of the Far Eastern Political party, a 3-homo sledging team with Lieutenant B.E.Southward. Ninnis, to survey Rex George V Land, Antarctica. On fourteen Dec 1912 Ninnis fell through a snow-covered crevasse along with virtually of the party's rations, and was never seen again. Their meagre provisions forced them to swallow their remaining dogs on their 507 km (315 mi) return journey. Their meat was tough, stringy and without a vestige of fat. Each brute yielded very piffling, and the major part was fed to the surviving dogs, which ate the meat, skin and bones until null remained.

Roald Amundsen, whose Antarctic expedition was planned effectually 97 sled dogs

The men also ate the canis familiaris'due south brains and livers. Unfortunately eating the liver of sled dogs produces the condition hypervitaminosis A because canines have a much higher tolerance for vitamin A than humans do. Mertz suffered a quick deterioration. He developed tum pains and became incapacitated and incoherent. On seven January 1913, Mertz died. Mawson continued lone, eventually making it back to camp alive.[22]

Roald Amundsen's expedition was planned around 97 sled dogs.[20] On his first attempt, two of his dogs froze to decease in the −56 °C (−69 °F) temperatures.[20] He tried a 2d fourth dimension and was successful.[20] Amundsen was covering 27 km (17 mi) a day, with stops every iv.8 km (iii mi) to build a cairn to mark the trail.[20] He had 55 dogs with him, which he culled until he had 14 left when he returned from the pole.[20] On the return trip, a man skied ahead of the dogs and hid meat in the cairns to encourage them to run.[xx]

Sled dog breeds [edit]

The original sled dogs were chosen for size, forcefulness and stamina, but modern dogs are bred for speed and endurance[nine] [14] Most sled dogs weigh around 25 kg (55 lb),[23] but they can weigh as petty equally 16 kg (35 lb), and can exceed 32 kg (71 lb).[fourteen] Sled dogs have a very efficient gait,[23] and "mushers strive for a well balanced dog team that matches all dogs for both size (approximately the same) and gait (the walking, trotting or running speeds of the dogs too every bit the 'transition speed' where a domestic dog will switch from one gait to another) so that the unabridged dog team moves in a like fashion which increases overall team efficiency."[14] They can sew together to 45 km/h (28 mph).[24] Because of this, sled dogs have very tough, webbed anxiety with closely spaced toes.[14] Their webbed feet deed as snowfall shoes.[xx]

Sled dog breeds can typically be divided into further sub-types:

- sprint dogs, bred to pull sleds speedily

- freight dogs, bred to pull massive weights

- long distance dogs, bred to travel hundreds or even thousands of miles, and

- sled laikas, Russian-bred to pull sleds besides equally herd reindeer and chase game.[25]

A canis familiaris's fur depends on its use. Freight dogs should take dense, warm coats to agree oestrus in,[14] and dart dogs have short coats that let heat out.[two] Most sled dogs have a double coat, with the outer coat keeping snow away from the torso, and a waterproof inner coat for insulation.[24] In warm weather condition, dogs may take issues regulating their body temperature and may overheat.[14] Their tails serve to protect their olfactory organ and anxiety from freezing when the domestic dog is curled up to slumber.[twenty] They also have a unique organisation of blood vessels in their legs to assist protect confronting frostbite.[xx]

Appetite is a big part of choosing sled dogs; picky dogs off trail may be pickier on the trail.[xiv] They are fed high-fat diets, and on the trail may eat oily salmon or blubbery body of water mammals.[20] Sled dogs also must not be overly ambitious with other dogs.[14] They also demand a lot of exercise.[26]

Breeds [edit]

Alaskan husky [edit]

The most commonly used dog in domestic dog sled racing,[23] the Alaskan husky is a mongrel[9] bred specifically for its performance as a sled dog.[2]

The first dogs arrived in the Americas 12,000 years ago; however, people and their dogs did not settle in the Arctic until the Paleo-Eskimo people four,500 years ago so the Thule people 1,000 years ago, both originating from Siberia.[27]

The word husky originated from the give-and-take referring to aboriginal Arctic people, in general, Eskimo, "...known every bit 'huskies', a contraction of 'Huskimos', the pronunciation given to the word 'Eskimos' past the English sailors of trading vessels.[28]" The use of husky is recorded from 1852 for dogs kept by Inuit people.[29]

In 2015, a written report using a number of genetic markers indicated that the Alaskan husky, the Siberian Croaking and the Alaskan Malamute share a close genetic relationship between each other and were related to Chukotka sled dogs from Siberia. They were separate from the two Inuit dogs, the Canadian Eskimo Dog and the Greenland domestic dog. In N America, the Siberian Croaking and the Alaskan Malamute both had maintained their Siberian lineage and had contributed significantly to the Alaskan croaking, which showed evidence of crossing with European dog breeds that was consequent with this breed being created in post-colonial North America. The modern Alaskan husky reflects 100 years or more of crossbreeding with English Pointers, German Shepherd Dogs and Salukis to better its performance.[27] Occasionally, Alaskan huskies are referred to as Indian Dogs, considering the all-time ones supposedly come from Native American villages in the Alaskan and Canadian interiors.[2] They typically weigh between eighteen and 34 kg (twoscore and 75 lb) and may have dumbo or sleek fur.[ii] Alaskan huskies bear trivial resemblance to the typical husky breeds they originated from, or to each other.[two]

There are two genetically distinct varieties of the Alaskan husky: a sprinting group and a long-altitude group.[xi] Alaskan Malamutes and Siberian Huskies contributed the about genetically to the long-distance group, while English Pointers and Salukis contributed the most to the sprinting grouping.[11] Anatolian Shepherd Dogs contributed a strong work ethic to both varieties.[11] There are many Alaskan huskies that are role Greyhound, which improves their speed.[2] Further crossbreeding of Alaskan huskies with German Shorthaired Pointers has given mode to another emerging mongrel sled dog known as the Eurohound.[30]

Alaskan Malamute [edit]

Alaskan Malamutes are large, stiff freight dogs.[ii] They counterbalance between 36 and 54 kg (eighty and 120 lb) and have round faces with soft features.[2] Freight dogs are a class of dogs that includes both full-blooded and non-pedigree dogs.[two] Alaskan Malamutes are thought to exist one of the commencement domesticated breeds of dogs, originating in the Kotzebue Sound region of Alaska.[31] These dogs are known for their broad chests, thick coats, and tough feet.[2] Speed has lilliputian to no value for these dogs - instead, the emphasis is on pulling strength.[two] They are used in expedition and long risk trips, and for hauling heavy loads.[two] Alaskan Malamutes were the dog of choice for hauling and messenger work in World War II.[31]

Canadian Eskimo Dog [edit]

The Canadian Eskimo Canis familiaris or Canadian Inuit Dog, also known as the Exquimaux Husky, Esquimaux Dog, and Qimmiq (an Inuit language word for dog), has its origins in the aboriginal sled dogs used past the Thule people of Arctic Canada.[32] The brood equally it exists today was primarily developed through the work of the Canadian regime.[32] Information technology is capable of pulling between 45 and 80 kg (99 and 176 lb) per dog for distances between 24 and 113 km (15 and seventy mi).[32] The Canadian Eskimo Dog was as well used every bit a hunting dog, helping Inuit hunters to catch seals, muskoxen, and polar bears.[32] On May ane, 2000, the Canadian territory of Nunavut officially adopted the "Canadian Inuit Dog" equally the animal symbol of the territory.[33] They are considered genetically to exist the aforementioned brood as the Greenland Dog, as research shows they have not even so diverged enough genetically to be considered separate breeds.[34]

Chinook [edit]

The Chinook is a rare breed of sled dog developed in New Hampshire in the early 1900s by Arthur Walden, a gold rush adventurer and dog driver, and is a blend of English Mastiff, Greenland Dog, German Shepherd Dog, and Belgian Shepherd.[35] It is the state dog of New Hampshire and was recognized by the American Kennel Club (AKC) in the Working Group in 2013.[35] They are described equally athletic and "hard bodied" with a "tireless gait".[35] Their coat colour is always tawny, ranging from a stake honey color to red-gold.

Greenland Canis familiaris [edit]

Greenland Dogs are heavy dogs with high endurance simply petty speed.[2] They are frequently used past people offering dog sled adventures and long expeditions.[2] As of 2016, there were virtually xv,000 Greenland Dogs living in Greenland, only decades ago the number was significantly higher and projects have been initiated to ensure the survival of the breed.[6] In many regions north of the Arctic Circumvolve in Greenland, they are a primary mode of transportation in the winter.[5] [36] Most hunters in Greenland favor domestic dog sled teams over snowmobiles, as the canis familiaris sled teams are more reliable.[36] They are considered genetically to be the same brood equally the Canadian Eskimo Canis familiaris, equally enquiry shows they have not yet diverged enough genetically to be considered separate breeds.[34]

Labrador Husky [edit]

The Labrador Husky originated in the Labrador portion of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. The breed probably arrived in the expanse with the Inuit people who came to Canada effectually 1300 AD. Despite the proper noun, Labrador huskies are not related to the Labrador retriever, but in fact nigh closely related the Canadian Eskimo Dog. At that place are estimated to be 50-threescore Labrador huskies in the earth.[37]

MacKenzie River Croaking [edit]

The term Mackenzie River husky describes several overlapping local populations of Chill and sub-Chill sled dog-blazon dogs, none of which constitutes a breed. Dogs from Yukon were crossed with large European breeds such as St. Bernards and Newfoundlands to create a powerful freighting dog capable of surviving harsh Arctic conditions.[38]

Samoyed [edit]

The Samoyed is a laika developed by the Samoyede people of Siberia, who used them to herd reindeer and hunt, in addition to hauling sleds.[39] These dogs were so prized, and the people who endemic them then dependent upon them for survival, that the dogs were allowed to sleep in the tents with their owners.[39] Samoyeds weigh about 20 to 29 kg (45 to 65 lb) pounds for males and 16 to 23 kg (35 to 50 lb) for females and stands from 48 to 60 cm (19 to 23.v in) at the shoulder.[39]

Stuffed Sakhalin Croaking "Jiro" on brandish

Sakhalin Husky [edit]

The Sakhalin Husky, also known every bit the Karafuto Ken (樺太犬), is a breed of sled dog adult on the island of Sakhalin. Sakhalin huskies are prized for their hardiness, great temperaments and easy trainability, even being the preferred dog used by the Soviet ground forces for hauling gear in harsh condition prior to World War II.[25] Unfortunately with the appearance of mechanized travel, Soviet officials determined that the cost of maintaining Sakhalins was wasteful and exterminated them, with only a handful residing in Nippon surviving.[25] Equally of 2015, there were just seven of these dogs left on their native island of Saghalien.[40]

2 Siberian Huskies in harness

Siberian Husky [edit]

Smaller than the similar-appearing Alaskan Malamute, the Siberian Husky pulls more, pound for pound, than a Malamute. Descendants of the sled dogs bred and used past the native Chukchi people of Siberia which were imported to Alaska in the early on 1900s, they were used as working dogs and racing sled dogs in Nome, Alaska throughout the 1910s, frequently dominating the All-Alaska Sweepstakes.[41] They afterwards became widely bred by recreational mushers and evidence-dog fanciers in the United States and Canada as the Siberian Croaking, after the popularity garnered from the 1925 serum run to Nome.[42] Siberians stand 20–23.v in (51–60 cm), counterbalance betwixt 35 and 60 lb (16 and 27 kg) (35–50 lb (16–23 kg) for females, 45–60 lb (20–27 kg) for males),[43] and have been selectively bred for both appearance and pulling ability.[two] They are even so used regularly today as sled dogs by competitive, recreational, and tour-guide mushers.[44]

Yakutian Laika [edit]

The Yakutian Laika (Russian: Якутская лайка) is an ancient working dog breed that originated in the Arctic seashore of the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic. In terms of functionality, Yakutian Laikas are a sled laika, being able to herd, hunt, and every bit well as haul freight. The Yakutian Laika is recognized by the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI)[45] and the AKC'due south Foundation Stock Service.[46] The Yakutian Laika is a medium size, strong and compact dog, with powerful muscles and thick double coat to handle biting Arctic temperatures.[47] They were the preferred canis familiaris of Russian polar explorer Georgy Ushakov, who prized them for their hardiness and versatility, being able to hunt seals and polar bears every bit well as haul sleds for thousands of miles.[25]

Other breeds [edit]

Numerous non-sled domestic dog breeds take been used as sled dogs. Poodles,[48] Irish Setters,[2] German Shorthaired Pointers,[2] Labrador Retrievers,[2] Newfoundlands,[12] Chow Chows and St. Bernards[12] accept all been used to pull sleds in the past.

World Championships [edit]

FSS held the beginning Earth Championships in Saint Moritz, Switzerland in 1990 with classes in just Sled Sprint (x-Dog, 8-Domestic dog, and six-Canis familiaris) and Skidog Pulka for men and women. 113 competitors arrived in the starting chutes to mark the momentous occasion. At get-go Globe Championships were held each year, but after the 1995 events, information technology was decided to concord them every ii years, which facilitated the bidding process and enabled the host organization more time for preparation.[49]

Famous sled dogs [edit]

Balto [edit]

Balto was the atomic number 82 domestic dog of the sled domestic dog team that carried the diphtheria serum on the last leg of the relay to Nome during the 1925 diphtheria epidemic.[fifty] He was driven by musher Gunnar Kaasen, who worked for Leonhard Seppala.[50] Seppala had as well bred Balto.[l]

In 1925, 10 months later on Balto completed his run,[51] a bronze statue was erected in his honour in Key Park near the Tisch Children'south Zoo.[52] The statue was sculpted past Frederick George Richard Roth.[52] Children ofttimes climb the statue to pretend to ride on the dog.[52] The plaque at the base of the statue reads "Endurance · Fidelity · Intelligence".[52] Balto's body was stuffed following his death in 1933, and is on display at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.[fifty]

In 1995, a Universal Pictures blithe movie based loosely on him, Balto, was released.[fifty] Roger Ebert gave information technology 3 out of 4 stars.[53]

Togo [edit]

Togo was the lead sled dog of Leonhard Seppala and his domestic dog sled squad in the 1925 serum run to Nome across key and northern Alaska. Seppala considered Togo to be the greatest sled dog and lead dog of his mushing career, and of that age in Alaska, stating in 1960: "I never had a better dog than Togo. His stamina, loyalty and intelligence could not be improved upon. Togo was the best domestic dog that ever traveled the Alaska trail."[54]

Katy Steinmetz in Time Magazine named Togo the most heroic beast of all fourth dimension, writing that "the dog that oftentimes gets credit for somewhen saving the town is Balto, but he simply happened to run the last, 55-mile leg in the race. The sled dog who did the king of beasts's share of the work was Togo. His journey, fraught with white-out storms, was the longest by 200 miles and included a traverse across perilous Norton Sound — where he saved his team and commuter in a courageous swim through ice floes."[55]

Togo would go along to become 1 of the foundation dogs for lines of Siberian sled dogs, and including eventually the Siberian Husky registered breed.[56]

Taro and Jiro [edit]

In 1958, an sick-fated Japanese research expedition to Antarctica fabricated an emergency evacuation, leaving behind 15 sled dogs. The researchers believed that a relief team would arrive within a few days, and so they left the dogs chained upwards outside with a minor supply of nutrient; however, the weather turned bad and the squad never made information technology to the outpost. I year later, a new trek arrived and discovered that two of the dogs, Taro and Jiro, had survived.[57] The breed spiked in popularity upon the release of the 1983 film Nankyoku Monogatari. A second film from 2006, Viii Beneath, provided a fictional version of the occurrence, but did not reference the breed. Instead, the motion picture features only eight dogs: two Alaskan Malamutes, and six Siberian Huskies.[58]

Other dogs [edit]

Anna was a pocket-sized sled dog who ran on Pam Flower'southward squad during her expedition to go the starting time woman to cross the Chill lone.[59] She was noted for being the smallest dog to run on the squad, and a picture book was created about her journey in the Arctic.[59]

In that location are numerous stories of blind sled dogs that go along to run, either on their own or with assistance from other dogs on the team.[24] [60]

See also [edit]

- List of sled dog races

- Sled domestic dog racing at the 1932 Winter Olympics

- Drafting dog

- Manhauling

References [edit]

- ^ Pitul'ko, Vladimir; Makeyev, Vjatcheslav (January 1991). "Ancient Arctic hunters". Nature. 349 (6308): 374. Bibcode:1991Natur.349..374P. doi:x.1038/349374a0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 5177152.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r south Cary, Bob (2009). Built-in to Pull: The Celebrity of Sled Dogs . Illustrated by Gail De Marcken. Minneapolis, Minnesota: U of Minnesota Printing. pp. 7–11. ISBN978-0816667734.

sled dogs.

- ^ Bogoslovskaya, L. South. "Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog International". thefanhitch.org . Retrieved 2021-09-04 .

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link) - ^ Pitulko, Vladimir V.; Kasparov, Aleksey M. (2017). "Archaeological dogs from the Early on Holocene Zhokhov site in the Eastern Siberian Arctic". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. xiii: 491–515. doi:ten.1016/j.jasrep.2017.04.003.

- ^ a b "Hold af slædehunde". Sullissivik. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Antallet af grønlandske slædehunde er halveret: Her er redningsplanen". Videnskab.dk. 25 July 2017. Retrieved 22 Dec 2019.

- ^ Marquard-Petersen, Ulf (2011). "Invasion of eastern Greenland by the high arctic wolf Canis lupus arctos". Wildlife Biology. 17 (4): 383–388. doi:10.2981/11-032. S2CID 84355723. Note: These figures are in the past because this was the time menses of interest for the wolf research conducted.

- ^ Ameen, Carly; Feuerborn, Tatiana R.; Brownish, Sarah K.; Linderholm, Anna; Hulme-Beaman, Ardern; Lebrasseur, Ophélie; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger South.; Lounsberry, Zachary T.; Lin, Audrey T.; Appelt, Martin; Bachmann, Lutz; Betts, Matthew; Britton, Kate; Darwent, John; Dietz, Rune; Fredholm, Merete; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Goriunova, Olga I.; Grønnow, Bjarne; Haile, James; Hallsson, Jón Hallsteinn; Harrison, Ramona; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Knecht, Rick; Losey, Robert J.; Masson-Maclean, Edouard; McGovern, Thomas H.; McManus-Fry, Ellen; Meldgaard, Morten; et al. (2019). "Specialized sledge dogs accompanied Inuit dispersal across the North American Arctic". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1916): 20191929. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1929. PMC6939252. PMID 31771471.

- ^ a b c d eastward f k h i j "Sled Dogs in the Northward". Yukon Quest Sled Dogs. Yukon Quest. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ Martin, Elizabeth Libbie (2012). Yukon Quest Sled Dog Race. Mount Pleasant, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 11. ISBN978-0738596273.

- ^ a b c d Huson, Heather J; Parker, Heidi G; Runstadler, Jonathan; Ostrander, Elaine A (July 2010). "A genetic autopsy of breed limerick and performance enhancement in the Alaskan sled dog". BMC Genetics. xi: 71. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-11-71. PMC2920855. PMID 20649949.

- ^ a b c d east f g h i j Hegener, Helen (June 2, 2011). "Dogsled mail in Alaska". Alaska Acceleration. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Young, Ian (2002). The Iditarod: Story of the Last Great Race. Illustrated past Timothy V. Rasinski. Capstone Classroom. pp. 5–13. ISBN073689523X.

- ^ a b c d e f one thousand h i "The Modern Sled Dog". Yukon Quest Sled Dogs. Yukon Quest. Archived from the original on December 26, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ "The Sledge Dogs of the Due north". Outing: Sport, Adventure, Travel, Fiction. West. B. Holland. 1901. pp. 130–137. Retrieved four March 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Lew Freedman; DeeDee Jonrowe (1995). "Introduction". Iditarod Dreams: A Year in the Life of Alaskan Sled Dog Racer DeeDee Jonrowe . Epicenter Press. pp. eleven–xv. ISBN978-0-945397-29-8 . Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ a b Lew Freedman; DeeDee Jonrowe (1995). "The Race Is On". Iditarod Dreams: A Year in the Life of Alaskan Sled Dog Racer DeeDee Jonrowe . Epicenter Press. pp. 25–33. ISBN978-0-945397-29-8 . Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Lew Freedman; DeeDee Jonrowe (1995). "The Starting Line". Iditarod Dreams: A Twelvemonth in the Life of Alaskan Sled Dog Racer DeeDee Jonrowe . Epicenter Printing. pp. 17–23. ISBN978-0-945397-29-8 . Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Janet Woolum (1998). "Susan Butcher (dog-sled racer)". Outstanding Women Athletes: Who They Are and How They Influenced Sports in America. Greenwood Publishing Grouping. pp. 94–96. ISBN978-one-57356-120-4 . Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d due east f g h i j yard l m n o p q r s t u v w x y William J. Mills (2003). Exploring Polar Frontiers: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 189–192. ISBN978-ane-57607-422-0 . Retrieved 27 Feb 2013.

- ^ "No Dogs Allowed". Polar Scientific discipline is Cool. 17 December 2012.

- ^ Douglas Mawson. "The Dwelling house of the Blizzard".

- ^ a b c "Sled Dogs: An Alaskan Epic". PBS. November 1999. Retrieved Feb 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c Person, Stephen (2011). Sled Dogs: Powerful Phenomenon . Bearport Publishing. pp. iv–ten. ISBN978-1617721342.

sled dogs.

- ^ a b c d RBTH, special to (2017-03-01). "Nordic spirit: Sled dogs of the Siberian North and the Far East". www.rbth.com . Retrieved 2021-07-26 .

- ^ "Humans and dogs have been sledding together for nearly 10,000 years". National Geographic Society. 25 June 2020.

- ^ a b Brown, Due south K; Darwent, C Chiliad; Wictum, Due east J; Sacks, B N (2015). "Using multiple markers to elucidate the aboriginal, historical and modern relationships among North American Arctic dog breeds". Heredity. 115 (6): 488–95. doi:10.1038/hdy.2015.49. PMC4806895. PMID 26103948.

- ^ George Morley Story, W. J. Kirwin, John David, Allison Widdowson (2004). Dictionary of Newfoundland English language. University of Toronto Press. p. 263. ISBN0-8020-6819-7.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Definition of HUSKY". www.merriam-webster.com . Retrieved 2021-12-23 .

- ^ News, Bryce Airgood Cadillac. "Sled dog racing, the 'loudest silent sport'". Cadillac News . Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ a b Betsy Sikora Siino (Jan 2007). Alaskan Malamutes. Barron'south Educational Series. pp. six–7. ISBN978-0-7641-3676-4 . Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Canadian Eskimo Canis familiaris". New Zealand Kennel Guild. Retrieved 2013-04-11 .

- ^ a b Hanne, Friis Andersen (2005). Population genetic assay of the Greenland dog and Canadian inuit dog : is information technology the same breed?. Purple Veterinarian and Agronomical Academy, Department of Animal Science and Fauna Health, Segmentation of Animal Genetics. OCLC 476638737.

- ^ a b c "AKC Recognizes Ii New Breeds for 2013". Dog Channel. February twenty, 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-11 .

- ^ a b Human being Planet – Arctic: Greenland sled dogs (Video). ABC1. March 10, 2011. Archived from the original on 2021-xi-18.

- ^ Hoyles, Samantha (December 1997). "The Bully Labrador Husky". Within Labrador: threescore–64.

- ^ MacQuarrie, Gordon (December 1997). "Kenai, Canis familiaris of Alaska". The Gordon MacQuarrie Sporting Treasury: 98–99.

- ^ a b c "Go To Know The Samoyed". Meet The Breed. American Kennel Society. Retrieved 2013-04-eleven .

- ^ "Desperate effort to save Sakhalin Laika from extinction on its native island". siberiantimes.com . Retrieved 2021-07-26 .

- ^ Thomas, Bob (2015). Leonhard Seppala : the Siberian canis familiaris and the golden age of sleddog racing 1908-1941. Pat Thomas. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company. ISBN978-1-57510-170-5. OCLC 931927411.

- ^ "The Siberian Husky: A Cursory History of the Breed in America". www.shca.org . Retrieved 2020-11-24 .

- ^ "The Standard for Siberian Huskies". world wide web.shca.org . Retrieved 2020-11-24 .

- ^ "Do many Siberian Huskies run the Iditarod? If non, why? – Iditarod". iditarod.com . Retrieved 2021-02-23 .

- ^ "Yakutskaya Laika".

- ^ "Foundation Stock Service® Programme Abode".

- ^ http://yakutian-laika.com/sites/default/files/docs/yakutskaya_layka_standart_na_russkom_dlya_publikacii_na_sayte_rkf_26.09.2019.pdf

- ^ Thornton, James S. (March 7, 1988). "The Very Latest In Mushing: Poodle-powered Sleds". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 2013-06-27 .

- ^ "History - International Federation of Sleddog Sports". world wide web.sleddogsport.internet . Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Sled Dogs: An Alaskan Epic: Balto". Nature. PBS. 21 November 1999. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ "Balto". Things To See. Fundamental Park Conservancy. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Balto". Attractions. Central Park.Com. Retrieved March four, 2013.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 22, 1995). "Balto". rogerebert.com. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ "Togo (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov . Retrieved 2021-09-14 .

- ^ Steinmetz, Katy (2011-03-21). "Height 10 Heroic Animals - Fourth dimension". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2021-09-14 .

- ^ 1949-, Thomas, Bob (2015). Leonhard Seppala : the Siberian canis familiaris and the gilded historic period of sleddog racing 1908-1941. Pictorial Histories Publishing Company. ISBN978-ane-57510-170-5. OCLC 931927411.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Saghalien Husky dogs who survived in Antarctica for a year". Kami-Ube Pediatric Dispensary. 2017-01-29. Retrieved 2021-07-28 .

- ^ "The Dogs in "Eight Beneath?" Not the Breed You Saw". National Purebred Dog Day. 2017-02-14. Retrieved 2021-07-28 .

- ^ a b Pam Flowers; Ann Dixon (one September 2003). Large-Enough Anna: The Piffling Sled Dog Who Braved The Arctic. Graphic Arts Centre Publishing Co. ISBN978-0-88240-580-3 . Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ The Associated Printing (Jan 25, 2013). "Gonzo, blind sled dog in New Hampshire, thrives in sled races with brother'south help". New York Daily News . Retrieved Feb xviii, 2013.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sled dogs. |

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sled_dog

0 Response to "How Many Pounds Can a Sled Dog Pull"

Post a Comment